Stained Glass

Stained glass is one of those things that plenty of people seem to like but few know much about. It has certainly been the case that art and architectural historians have routinely held a lot of Victorian stained glass in low regard, sometimes with good reason, but that view hasn’t always been shared by the members of church congregations who remain unshakeably attached to the windows in their places of worship.

There remains a certain reverence for medieval glass, although its chief virtue is sometimes only the fact that it is old, and has, against the odds, survived. However, medieval glass has a palpable authenticity that inevitably ranks it above much of the revivalist stained glass of the nineteenth century.

Since the 1970s there has been a slow growth in the appreciation of the qualities of some of the better Victorian glass and particularly of the Arts and Crafts glass of the late nineteenth century and the earlier twentieth century. The available information about these artists and studios has gradually increased with the production of books and articles, as well as online resources in recent years.

A multitude of stories lies behind the commissioning and manufacture of stained glass windows for churches, which can sometimes be found in the correspondence between the patrons, committees, designers and studios. The meanings of pictorial windows are often complex, layering texts and images with theological sophistication, and the techniques of making, painting and assembling the windows involve much skill and sometimes innovation. Regardless of the artistic merit of stained glass throughout the ages, these works of public art are undoubtedly complex cultural objects that need to be properly understood.

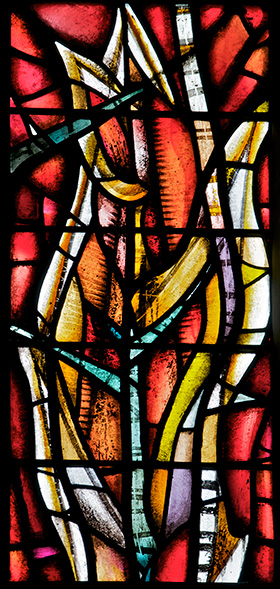

Since the 1960s there has been considerable innovation in the making of works in glass for windows that go beyond the painting, staining and leading together of pieces of white, clear and coloured glass. This innovation has been particularly noticeable in commissions for the use of architectural glass outside of places of worship, but has sometimes resulted in works for churches that fall outside of the strict definition of ‘stained glass’, but remain works of stained glass according to contemporary understanding of the term.

Examples of outstanding stained glass can be found in all periods. The most celebrated windows are usually designed by artists better known for their work in other media, such as William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall and John Piper. But further excellent works of art were made by twentieth-century artists working in glass such as Karl Parsons, Wilhelmina Geddes, Douglas Strachan and Lawrence Lee. These artists often looked back to the power and conviction that they found in the late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century windows of northern France.

Despite the interest in stained glass, much remains unknown about most of the commercial firms and individual artists that made stained glass windows. Each new study of the windows of a particular building, or of an artist or studio, potentially makes an important contribution to the study of the artform and helps inform new work on other buildings and makers.

Sulien Books

art and craft, ancient and modern